CMV retinitis

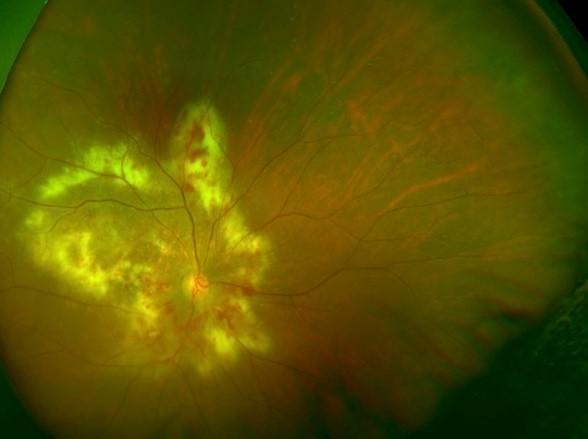

In the ‘pre-HAART era’, CMV retinitis affected up to 40% of people with AIDS, but usually only when CD4+ T cell counts were <50/mL (Figure 4a). Since the advent of combination antiretroviral therapy (ART), there has been a dramatic reduction in the incidence of CMV retinitis. Clinical features include floaters and decreased visual acuity and/or field loss. Vitritis is usually mild orabsent. CMV retinitis may be either 1) haemorrhagic (associated with necrosis), with loss of fundal details (‘pizza pie’ appearance - Figure 4b), 2) granular, which is relatively indolent with minimal haemorrhage and vascular sheathing, 3) perivascular, seen as ‘frosted branch angiitis’ which spreads along the course of the retinal vessels. It may be asymptomatic and consequently, regular screening should be performed in patients at risk of CMV infection. Complications include retinal detachment (up to 30% of patients), retinal atrophy, and optic nerve disease (5%) {ref} Singalavanija T, Ausayakhun S, Tangmonkongvoragul C. Anterior segment and external ocular disorders associated with HIV infections in the era of HAART in Chiang Mai University Hospital, a prospective descriptive cross sectional study. PLoS One. 2018;13(2) {/ref}.

CMV retinitis is usually treated with systemic antivirals (Table 4). Intravitreal foscarnet or ganciclovir is often used, particulalry when the macula and optic disc are involved. ART is an essential component of overall management; however timing of ART should be discussed between an HIV physician and ophthalmologist. Anti-CMV secondary prophylaxis is continued until the CD4+ T cell count is >100/mL for three to six months. If stopped prior to this time. the patient is at increased risk of immune reconstitution uveitis. Lifelong maintenance treatment is recommended for all patients without immune recovery.

Table 4. Systemic antiviral therapy for CMV and HSV ocular disease

|

Condition |

Treatment |

Duration |

|

CMV infection - systemic therapy |

Valganciclovir 900mg orally q12h loading then 450mg BD OR Ganciclovir 5mg/kg q12h intravenous OR Foscarnet 90mg/kg q12h intravenous OR Cidofovir 5mg/kg weekly |

14 to 21 days until required 14-21 days 14-21 days 14 days |

|

CMV retinitis |

In addition to above: Management by an ophthalmologist: Ganciclovir 4mg/0.1ml per injection, 1-4 doses |

Initial, then as needed |

|

Herpetic retinitis |

Management by an ophthalmologist: Intravitreal foscarnet 2.4mg/0.1mL WITH aciclovir IV dose 5-10mg/kg/d WITH systemic steroid 1mg/kg then acyclovir orally PO 400–800mg 5x/day OR valaciclovir 2g q8ha then valaciclovir 1g q8h then valaciclovir 500mg q8h |

Initial 2 weeks tapering steroid dose 6 weeks 10 days 14 days until required |

- a) This dose is well documented and utilised routinely on the basis that this is as efficient as intravenous acyclovir 10 mg/kg tds without exposing patients to the side-effects associated with higher doses of valacyclovir {ref} Beutner KR. Valacyclovir: a review of its antiviral activity, pharmacokinetic properties, and clinical efficac Antiviral Res. 1995;28:281-90 {/ref}

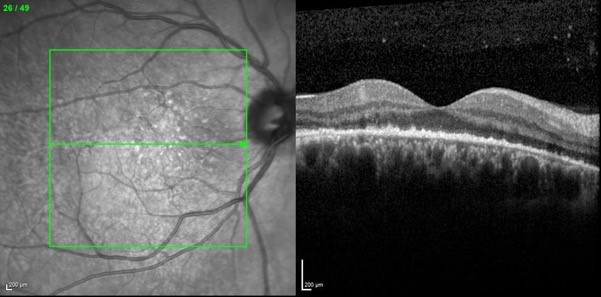

Figure 4a. Optos colour fundus image of the right eye of a patient with CMV retinitis with newly diagnosed HIV infection and a CD4+ T cell count of 30/mL.

Source: Uveitis Department Sydney Eye Hospital, used with permission.

Herpetic viral uveitis acute retinal necrosis

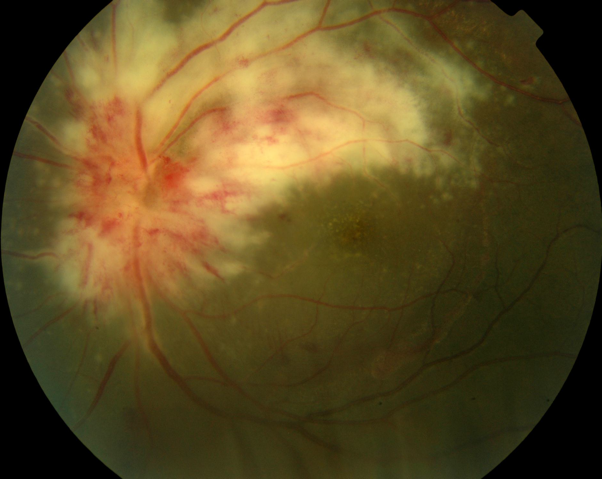

This rare syndrome of acute retinal necrosis is caused by VZV, HSV-1 or HSV-2 infection (Table 5). It may occur in the both the immunocompromised as well as healthy individuals of any age (Figure 5 and 6). Clinical findings include either unilateral or bilateral decrease in visual acuity, floaters and discomfort {ref} Ning BK, Kelly SP, Chu C, E M. Sequential retinal necrosis secondary to varicella zoster in unrecognised long-standing HIV infection: patient safety report. BMJ Case Rep. 2018 {/ref}. It is predominantly a peripheral disease comprising occlusive arteritis, full-thickness peripheral necrotizing retinitis (well demarcated, spread circumferentially), marked vitritis and anterior chamber activity. Complications include retinal detachment (in up to 75%; rhegmatogenous or tractional) and ischaemic optic neuropathy. Second eye involvement occurs in around 30% and may occur simultaneously or up to several years later.

Figure 5. Optos widefield colour fundus image of the left eye of a patient with HSV retinitis

Source: Uveitis Department Sydney Eye Hospital, used with permission.

Herpetic viral uveitis acute retinal necrosis

This rare syndrome of acute retinal necrosis is caused by VZV, HSV-1 or HSV-2 infection (Table 5). It may occur in the both the immunocompromised as well as healthy individuals of any age (Figure 5 and 6). Clinical findings include either unilateral or bilateral decrease in visual acuity, floaters and discomfort {ref} Ning BK, Kelly SP, Chu C, E M. Sequential retinal necrosis secondary to varicella zoster in unrecognised long-standing HIV infection: patient safety report. BMJ Case Rep. 2018 {/ref}. It is predominantly a peripheral disease comprising occlusive arteritis, full-thickness peripheral necrotizing retinitis (well demarcated, spread circumferentially), marked vitritis and anterior chamber activity. Complications include retinal detachment (in up to 75%; rhegmatogenous or tractional) and ischaemic optic neuropathy. Second eye involvement occurs in around 30% and may occur simultaneously or up to several years later.

Figure 5. Optos widefield colour fundus image of the left eye of a patient with HSV retinitis

Source: Uveitis Department, Sydney Eye Hospital, with permission.

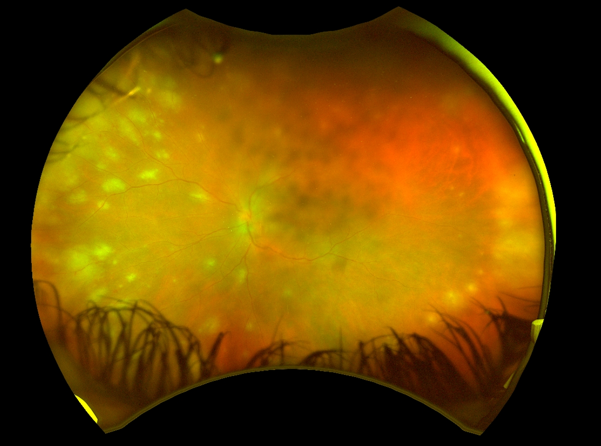

Figure 6. Optos widefield colour fundus image of the left eye of a patient with VZV retinitis highlighting a large amount of vitritis

Source: Uveitis Department, Sydney Eye Hospital, with permission.

All patients with clinically suspected herpetic retinitis are treated with intravitreal foscarnet 2.4mg/0.1mL as initial treatment, then a combination of antivirals and systemic corticosteroids to treat the inflammation (Table 4). Retinal detachment repair is challenging due to the necrotic retina and number of breaks; vitrectomy with silicone oil injection is usually needed.

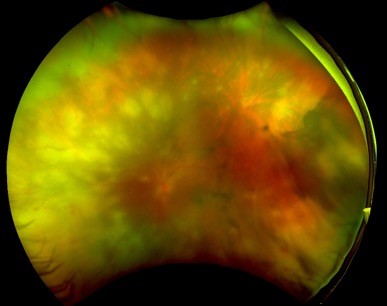

Progressive outer retinal necrosis

Progressive outer retinal necrosis (PORN) is a very rare devastating necrotizing retinitis caused by VZV infection in advanced HIV infection (usually with CD4+ T-cell counts <50/mL) (Table 5). Clinical findings include bilateral, painless, rapid decrease in visual acuity. Retinal examination reveals rapidly coalescing white areas of outer retinal necrosis (often central as well as peripheral) but with minimal vasculitis, retinitis, or vitritis (Figure 7). Treatment is similar to above {ref}Lo PF, Lim R, Antonakis SN, Almeida GC. Progressive outer retinal necrosis: manifestation of human immunodeficiency virus infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;May 6 {/ref}.

Figure 7. Colour fundus photo of the left eye showing progressive outer retinal necrosis

Source: Uveitis Department Sydney Eye Hospital, with permission.

Table 5. Diagnostic criteria for ARN, PORN and CMV retinitis1

|

ARN |

PORN |

CMV retinitis |

|

|

Appearance |

One or more foci of full thickness retinal necrosis |

Multiple foci of deep retinal opacification which may be confluent |

Creamy ‘brush-fire’ (along vessels) retinitis + haemorhage and hard exudate (‘Pizza fundus’) +/- Papilitis |

|

Location |

Peripheral retina (usually adjacent outside arcades) |

Peripheral retina Macula involvement |

Begins anywhere in the retina |

|

Progression |

Rapid but usually responds to treatment |

Extremely rapid |

Slow; 1 Disc Diameter every 3 weeks, painless |

|

Direction |

Circumferential |

No consistent direction |

No consistent direction |

|

Vessels |

Occlusive vasculopathy (arterial) |

No vascular inflammation |

Occlusive periphlebitis à sheathing (frosted branch angiitis) |

|

Inflammation |

Prominent anterior chamber and vitreous inflammation |

Minimal or none |

Minimal |

|

Suggestive features |

Optic neuropathy / atrophy Scleritis Pain |

Perivenular clearing of retinal opacification |

Haemorhage, which leaves behind thin fibroglial scar |

- {ref} Denniston AKO, PL M. Oxford Handbook of Ophthalmology. 3rd edition ed. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2014 {/ref}

Syphilis

Syphilis affecting the eye may be unilateral or bilateral, unifocal or multifocal and cause numerous types of ocular inflammation (Table 6), including retinitis, chorioretinitis, yellow plaque-like lesions at the level of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium (RPE) (Figure 8a,8b,8c) with overlying vitritis and serous retinal detachment and optic peri-neuritis (Figure 9). Resolution of the lesions results in a pigmentary retinopathy. Serum should be tested for antibodies to Treponema. pallidum as evidence of current or previous T. pallidum infection and for ‘non-treponemal antibodies’ (RPR, VDRL) to assess disease stage or treatment response. Management of syphilitic eye disease should be undertaken in conjunction with an infectious disease or sexual health physician as treatment requires high-dose penicillin, with an extended regimen for late latent and tertiary syphilis. Spirochete death may transiently worsen inflammation (Jarisch-Herxheimer or J-H reaction). Systemic steroids may also be used to treat the paradoxical J-H reaction and the intraocular and/or optic nerve inflammatory response {ref} Argemi X, Hansmann Y, Martin M, Lefebvre N, Douiri N, Christmann D, et al. Neurosyphilis: A retrospective study of 13 cases at Strasbourg University Hospital. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2017;40(8):654-60 {/ref}.

Table 6. Ophthalmic complications of syphilis1

|

Anterior segment |

Conjunctival chancre Pupillary conjunctivitis Episcleritis scleritis Interstitial Keratitis Anterior uveitis |

|

Posterior segment |

Multi-/ unifocal choroiditis/ chorioretinitis Neuroretinitis Retinal vasculitis |

|

Neuro-ophthalmic |

Argyll Robertson Pupils Papilloedema Retrobulbar neuritis optic peri-neuritis Ocular motility disorders Visual Field defects |

- {ref} Denniston AKO, PL M. OXford Handbook of Ophthalmology. 3rd edition ed. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2014 {/ref}

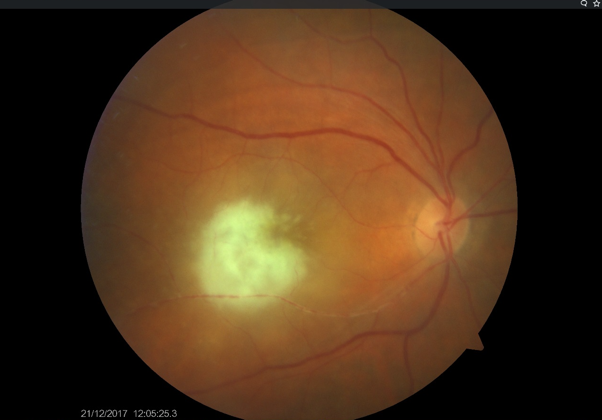

Figure 8a. Acute syphilitic posterior placoid chorioretinitis (ASPPC) of the right eye in a newly diagnosed patient with HIV infection

Figure 8b. ASPPC in the same patient in the right eye on fundal autofluorescence

Figure 8c. OCT image in the same patient highlighting the hyperreflective nodularity of the choroid-retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) complex with focal disruption of the overlying photoreceptor inner-outer segment junction in the areas seen on the colour and autofluorescence image. Changes along the RPE improved after antibiotic treatment.

Source: Uveitis Department Sydney Eye Hospital, with permission.

Figure 9. Colour fundus photo of the left eye highlighting perioptic neuritis secondary to syphilis infection.

Source: Uveitis Department Sydney Eye Hospital, with permission.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis and HIV infection are common co-infections in sub-Saharan Africa and other parts of the developing world but are uncommon in the developed world unless there are additional risk factors for TB. The ocular manifestations of TB can be protean and depend on the exact pattern of systemic Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Posterior segment involvement by TB can include vitritis, occlusive retinal vasculitis (periphlebitis, ischaemia, neovascularization and haemorrhage), macula oedema, choroidal granulomata (usually multifocal around the posterior pole), serpiginous choroidopathy and optic neuropathy. Investigations for systemic TB should be performed, although ocular TB may occur without evidence of active, infectious extra-ocular disease (ie sputum cultures, chest X-ray and whole blood interferon gamma release assay or tuberculin skin test). While PCR testing and culture of aqueous or vitreous fluid may be attempted, they are of low yield and the diagnosis is usually made on clinical grounds. Treatment is with a standard four drug regimen +/- localised treatment of disease complications. Visual acuity should be checked before starting treatment with ethambutol and the patient advised to report any disturbance of visual acuity, colour vision or visual fields.

Toxoplasma retinochoroiditis

Ocular infections by Toxoplasma gondii are decreasing in frequency due to the use of ART and the anti-toxoplasma efficacy of pneumocystis pneumonia prophylaxis. However, when it does occur, ocular toxoplasmosis in patients with HIV infection is more severe than in HIV seronegative subjects and often multifocal (even bilateral), associated with moderate/severe anterior uveitis and vitritis, and commonly associated with neuro-toxoplasmosis. In contrast to immunocompetent individuals, it always requires treatment. Corticosteroids, if used, should be used extremely cautiously.

Ocular toxoplasmosis may include anterior uveitis (often with high intraocular pressure and Keratic Precipitates), vitritis (may have ‘vitreous precipitates’ on the posterior surface of a posterior vitreous detachment), retinitis and retinal vasculitis (periphlebitis). Other presentations include: scleritis, punctate outer retinitis (with quiet vitreous), large lesions, endophthalmitis-like, neuroretinitis, serous retinal detachments, pigmentary retinopathy. HIV-positive individuals may have life-threatening disease, including encephalitis, intracerebral cysts, hepatitis and myocarditis {ref} Tsen CL, Chen SC, Chen YS, Sheu SJ. Uveitis as an initial manifestation of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Int J STD AIDS. 2017;28(12):1224-8 {/ref}. Toxoplasma retinitis appears as a white, fluffy circumscribed area of retinitis when active (Figure 10) and becomes pigmented as it heals to form an atrophic scar. Active satellite lesions often develop adjacent to old scars.

Figure 10. Fundal image showing focus of toxoplasmic retinitis and associated retinal vasculitis in the right eye.

Source: Uveitis Department Sydney Eye Hospital, with permission.

Toxoplasma retinochoroiditis is essentially a clinical diagnosis. Positive serological tests must be interpreted with caution as the majority of the adult population has anti-Toxoplasma IgG antibodies from previous exposure. Although IgM antibodies are suggestive of recently acquired infection, there may be IgM cross reactivity and persistence. Negative serology in undiluted serum makes the diagnosis unlikely. Detection of Toxoplasma DNA by PCR in intraocular fluids can be very useful diagnostically. Systemic treatment varies depending on severity of HIV associated immunosuppression. The mainstay of treatment is pyrimethamine with sulfadiazine, clindamycin or atovaquone. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole is an alternate agent. Steroids should be used very cautiously in HIV / immunosuppressed individuals.